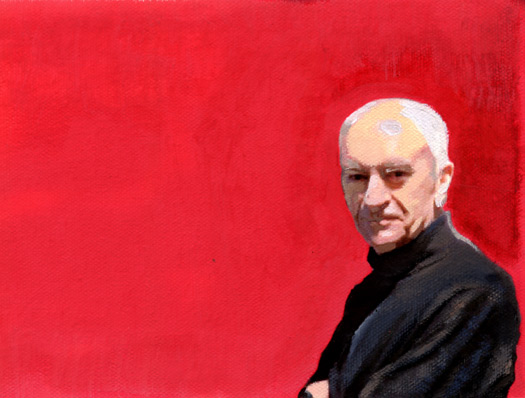

Iconic Designer Massimo Vignelli on Intellectual Elegance, Education, and Love

by Maria Popova

“Intellectual elegance [is] a mind that is continually refining itself with education and knowledge. Intellectual elegance is the opposite of intellectual vulgarity.”

Besides the iconic New York City subway map, for which he remains best-known, the great Massimo Vignelli has worked on some of the twentieth century’s most memorable packaging, identity, and public signage for clients like IBM, American Airlines, and Bloomingdale’s, and has earned some of the creative industry’s most prestigious awards, including the AIGA Gold Medal (1983), the New York State Governor’s Award for Excellence (1993), the National Arts Club Gold Medal for Design (2004), and the Lifetime Achievement Award from the Cooper Hewitt National Design Museum (2005). But nowhere do Vignelli’s eloquence, wisdom, earnestness, and sensitivity shine more brilliantly than in How to Think Like a Great Graphic Designer (public library) — the same fantastic anthology of Debbie Millman‘s interviews with creative icons that gave usPaula Scher’s slot machine metaphor for creativity.

Besides the iconic New York City subway map, for which he remains best-known, the great Massimo Vignelli has worked on some of the twentieth century’s most memorable packaging, identity, and public signage for clients like IBM, American Airlines, and Bloomingdale’s, and has earned some of the creative industry’s most prestigious awards, including the AIGA Gold Medal (1983), the New York State Governor’s Award for Excellence (1993), the National Arts Club Gold Medal for Design (2004), and the Lifetime Achievement Award from the Cooper Hewitt National Design Museum (2005). But nowhere do Vignelli’s eloquence, wisdom, earnestness, and sensitivity shine more brilliantly than in How to Think Like a Great Graphic Designer (public library) — the same fantastic anthology of Debbie Millman‘s interviews with creative icons that gave usPaula Scher’s slot machine metaphor for creativity.

A champion of “intellectual elegance,” Vignelli explains his lifelong crusade against vulgarity:

MV: When I talk about elegance, I mean intellectual elegance. Elegance of the mind.

DM: How would you define elegance of the mind?

MV: I would define intellectual elegance as a mind that is continually refining itself with education and knowledge. Intellectual elegance is the opposite of intellectual vulgarity. We all know vulgarity very well. Elegance is the opposite.

DM: I have to ask: What would you consider to be vulgar?

MV: Vulgarity is something underneath culture and education. Anything that is not refined.

[…]

DM: Why do you think people are fascinated by vulgarity?

MV: Because it is easier to absorb. Elegance is about education and refinement, and it is a by-product of a continual search for the best and for the sublime. And it is a continuous refusal of indulging in anything that is vulgar. It’s a job.

He offers an articulate definition of what design is really about:

It is to decrease the amount of vulgarity in the world. It is to make the world a better place to be. But everything is relative. There is a certain amount of latitude between what is good, what is elegant, and what is refined that can take many, many manifestations. It doesn’t have to be one style. We’re not talking about style, we’re talking about quality. Style is tangible, quality is intangible. I am talking about creating for everything that surrounds us a level of quality.

Like Steve Jobs famously did, Vignelli has profound disdain for focus groups and, like Millman herself, advocates for not letting limited imagination shrink the boundaries of the possible:

I don’t believe in market research. I don’t believe in marketing the way it’s done in America. The American way of marketing is to answer to the wants of the customer instead of answering to the needs of the customer. The purpose of marketing should be to find needs — not to find wants.

People do not know what they want. They barely know what they need, but they definitely do not know what they want. They’re conditioned by the limited imagination of what is possible. … Most of the time, focus groups are built on the pressure of ignorance.

Vignelli adds to history’s most beautiful definitions of love:

MV: Love is a cake that comes in layers. The top layer is the most appealing one. This is the one you see first. Then you cut into it and you see many different layers. They’re all beautiful, but some are sweeter than others.

How do I define love? I define it as a very intense passion on the one hand, and a very steady level on the other. The first layer, the one of passion, is the most troublesome. God, it’s a pain.

DM: Why?

MV: Because the more you love, the more jealous you get. You become jealous of everything, the air around the person, the people, a look, even the way they look at something. Then there is the extreme pleasure of writing about love, as well. This is fascinating to me. The layer of correspondence — and the anxiety to receive answers. That is great.

Finally you come to the physical layer. The emotion of receiving and conveying pleasure is sensational. It’s unbelievable how your entire body becomes a messenger. Your fingers, lips, eyes, smells. Your whole body becomes involved.

Then there is the layer of suffering. Distance, remoteness, no presence, horror. The suffering of not seeing who you want to see, and not being with whom you love. This is another painful aspect of love. We are talking about pain. All these layers define love. I think that is why it’s so great and so extremely complex.

Like other great creators, including Paula Scher, William Gibson, and Henry Miller, Vignelli recognizes the combinatorial quality of creative work as a sum-total of one’s lived experience:

One of the great advantages of being so concentrated on your work is that it is all there is. Everything I do comes into this and enriches me. Everything, even every book I read, enriches me.

On the life of purpose:

DM: Do you think that there’s a common denominator to people who can make a great contribution? Do you think that there’s something that–

MV: Unites them? Yes. What in Greek is called sympathy, the synchronization of pathos. You feel this incredible level of connection with these people. To a certain extent, it is equally comparable to love.

On the poetics of New York, echoing Anaïs Nin:

New York is a fabulous city. It’s like a magnet. I can’t leave anymore. There is nothing that can compare to New York. And it is not even beautiful. There are hundreds, thousands of other cities that are much more beautiful. But there is only one New York.

On design vs. art:

DM: How do you generally start a project?

MV: By listening as much as I can. I am convinced the solution is always in the problem. You could do a design that you like, but it doesn’t solve the problem. Design must solve a problem. Then, the design is exciting. But I find it extremely difficult. This is why I respect artists. Without a problem, I don’t exist. Artists are lucky; they can work by themselves. They don’t need a problem